It’s a bad fish

Making our way to Tanga, with the coelacanth in the boot, Simon, The Observer's driver from Dar es Salaam, was deeply unimpressed with his unexpected passenger. He produced a pink bottle of rose poppy perfume and sprayed it liberally around the car to mask the odour seeping in.

'Why should they save this fish?' he demanded. 'This is not a good fish. It's oily and you cannot eat this, and it's a smelly fish.' Fixing me with a puzzled look, he concluded: 'It's a bad fish.'

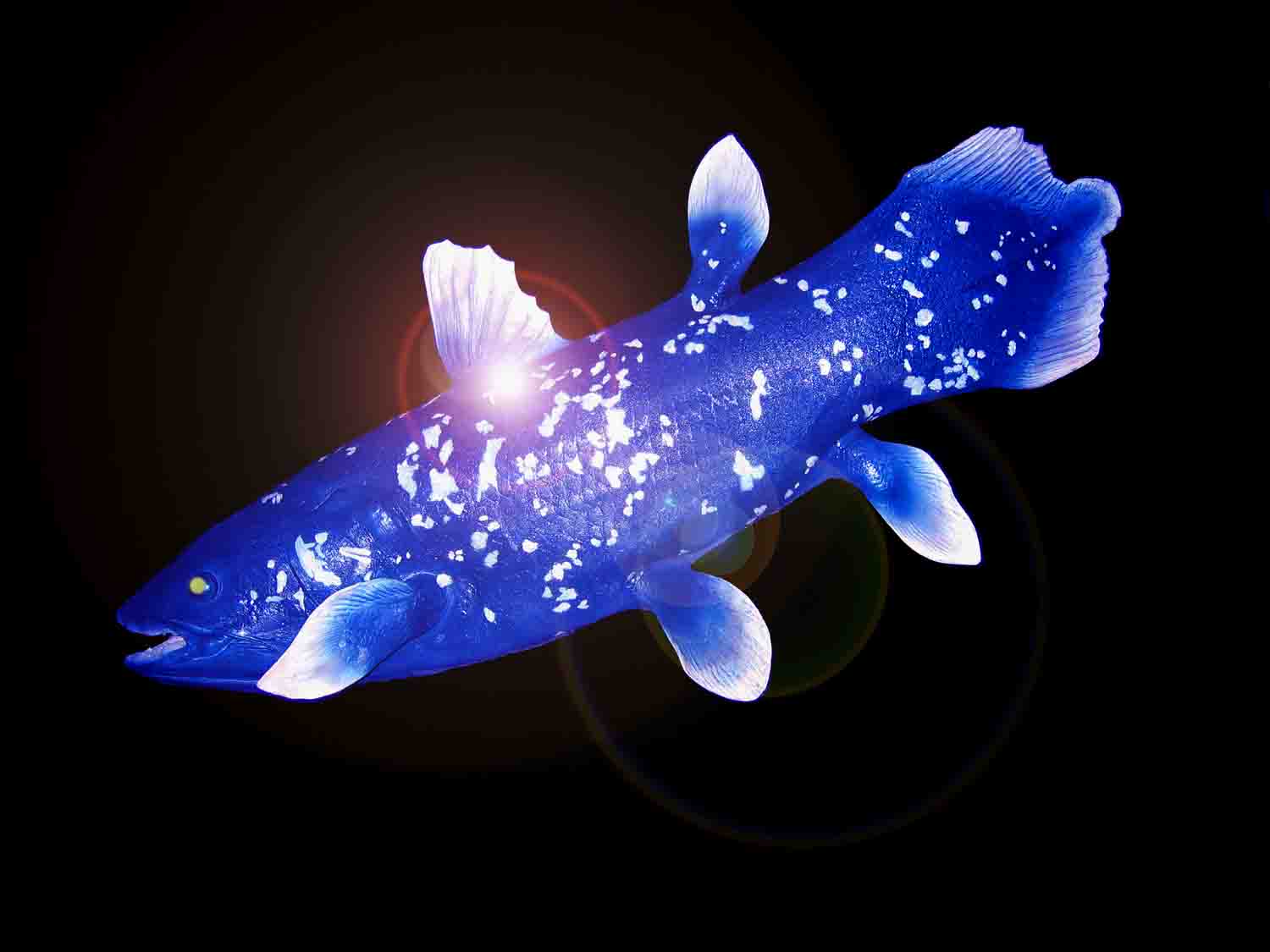

What if the soul of Gaia were stored in the coelacanth, a fish of ancient provenance and superbly adaptable evolved phenotype -- as oily fresh today as when the first one rolled off the line 400 million years ago?

Being a Chimpus Grinnus, you would eat it, nasty nictitating opposable thumb smearing organic tartar sauce across this elegantly spineless dinosaur fish before sliding it into your eager maw.

There isn’t any one thing that will break the back of the global ecosystem. Running out of fish? Why worry, we’ve got plenty of algae if we start to get hungry! Who will weep for the coelacanth, the dodo of the sea? If not a cabbie in the Port of Peace, who?

The beflowered gamboling ghosts of the Neanderthals hardly count, their disapproving furrowed brows casting huge shadows over our fried food shacks and Hummers.

Bitter, they are, after Homo Sapien Sapien spearchucked every last one of them, and made frisbees out of their braincases.

Imagine their confusion, “Oogl fop Gorp???” when modern humans finally run out of white-meat fish, yet still sit in McPappies with a shit-eating grin, swallering chunks of some mud-hungry dankfish ripped from the very ocean floor, then bleached corpse white. Katchup helps.

At the rate the Earth Services are being consumed, some time around 2019 the confused muttering of the spirit hominids dancing in the misty wind behind the dumpster will fade, instantly replaced by a moment of Satori for the remaining human species:

“Oh Shit. We ate the world, and there be nothing left but weeds.”

PLANET OF WEEDS

My own guess about the mid-term future, excused by no exemption, is that our Planet of Weeds will indeed be a crummier place, a lonelier and uglier place, and a particularly wretched place for the 2 billion people comprising Alan Durning's absolute poor. What will increase most dramatically as time proceeds, I suspect, won't be generalized misery or futuristic modes of consumption but the gulf between two global classes experiencing those extremes. Progressive failure of ecosystem functions? Yes, but human resourcefulness of the sort Julian Simon so admired will probably find stopgap technological remedies, to be available for a price.

So the world's privileged class--that's your class and my class--will probably still manage to maintain themselves inside Homer-Dixon's stretch limo, drinking bottled water and breathing bottled air and eating reasonably healthy food that has become incredibly precious, while the potholes on the road outside grow ever deeper.

Eventually the limo will look more like a lunar rover. Ragtag mobs of desperate souls will cling to its bumpers, like groupies on Elvis's final Cadillac. The absolute poor will suffer their lack of ecological privilege in the form of lowered life expectancy, bad health, absence of education, corrosive want, and anger. Maybe in time they'll find ways to gather themselves in localized revolt against the affluent class. Not likely, though, as long as affluence buys guns. In any case, well before that they will have burned the last stick of Bornean dipterocarp for firewood and roasted the last lemur, the last grizzly bear, the last elephant left unprotected outside a zoo.

Jablonski has a hundred things to do before leaving for Alaska, so after two hours I clear out. The heat on the sidewalk is fierce, though not nearly as fierce as this summer's heat in New Delhi or Dallas, where people are dying. Since my flight doesn't leave until early evening, I cab downtown and take refuge in a nouveau-Cajun restaurant near the river. Over a beer and jambalaya, I glance again at Jablonski's Science paper, titled "Extinctions: A Paleontological Perspective." I also play back the tape of our conversation, pressing my ear against the little recorder to hear it over the lunch-crowd noise.

Among the last questions I asked Jablonski was, What will happen after this mass extinction, assuming it proceeds to a worst-case scenario? If we destroy half or two thirds of all living species, how long will it take for evolution to fill the planet back up? "I don't know the answer to that," he said. "I'd rather not bottom out and see what happens next." In the journal paper he had hazarded that, based on fossil evidence in rock laid down atop the K-T event and others, the time required for full recovery might be 5 or 10 million years. From a paleontological perspective, that's fast. "Biotic recoveries after mass extinctions are geologically rapid but immensely prolonged on human time scales," he wrote.

There was also the proviso, cited from another expert, that recovery might not begin until after the extinction-causing circumstances have disappeared. But in this case, of course, the circumstances won't likely disappear until we do.

Needless to say, shithead, if you happen to see a coelacanth swim by, whether confined in the auspices of your wading pool or frolicking off the coast of northern, Tanzania, pat the little fucker on the head and give her a shotgun.

For Stupidity, that fierce predator, is loose on the watery rockball.

"I don't know, I can imagine quite a bit." -- Han Solo.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home